"To Pimp a Butterfly": A Track-By-Track Sketch to Encourage Finding the Larger Narrative

- Cole Schneider

- Jan 14, 2016

- 20 min read

The Movietown blog is going MUSICtown today, as I've sketched a rough analysis of Kendrick Lamar's already classic, "To Pimp a Butterfly". If you have somehow not yet heard the album, forget this post right now and go find it. If you have heard the album, then you will understand that it is an immense musical, literary, and social work, the kind of work that demands its listeners attention. It has earned the oppurtunity to be more carefully disected so below I have sketched out the story, taking his words track-by-track to uncover the larger story, themes, and purpose. I mostly avoid talking about the actual music and vocal delivery of the album (which is stunning, soulful, and skillful); this post is about story, and story is the backbone to film as well as music, as well as theater, etc.

To avoid abuse of the MOVIEtown brand, I hope you will find the sketch to have a kind of cinematic unfurling, and I've included small notes and asides that reference movie things. I would also encourage fans of the album to find Spike Lee's most recent joint, "Chi-Raq", which has "To Pimp a Butterfly" character Wesley Snipes playing a hilarious character against-type and which deals with some of the same ideas Kendrick does, but in a very different way. It's smart, funny, stylish and built on a similar social awareness that acknowleges hope amidst trouble. "Chi-Raq" is one of the best films of 2015, but this post isn't about "Chi-Raq". This post, though, is about Kendrick Lamar's, "To Pimp a Butterfly", which is one of the best albums of ALL-TIME. I hope you enjoy the article a tenth of a percent as much as I've enjoyed this album.

The Cast

Lead Characters

2Pac

Compton

God

Lucy

Niggas* (Kendrick)

Uncle Sam

Notable Supporting Characters

The boy(s)

Dead friend

Dr. Dre

His friends

Homeless man

King Kunta Kinte

Momma

Murderer

Nelson Mandela

Trayvon Martin

Wesley Snipes

Whitney Alford

The woman

*Cole is a white man who does not in any way condone the derogative use of this term, but he's using it for this article in order to maintain the authenticity of Kendrick's voice in the spirit of his album, and especially in light of his explanation of the word on “i”.

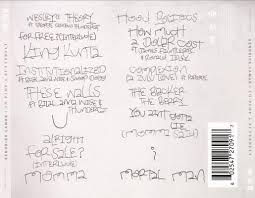

The Narrative Structure

Act I—Uncle Sam Invades Compton

Scene I: Wesley's Theory

Scene II: For Free? (Interlude)

Act II—The Nigga's Plight

Scene I: King Kunta

Scene II: Institutionalized

Scene III: These Walls

Scene IV: u

Scene V: Alright

Act III—God and the Devil

Scene I: For Sale? (Interlude)

Scene II: Momma

Scene III: Hood Politics

Scene IV: How Much a Dollar Cost

Act IV—A Nigga's Place In the World

Scene I: Complexion (A Zulu Love)

Scene II: The Blacker the Berry

Scene III: You Ain't Gotta Lie (Momma Said)

Act V—A Post-2Pac World

Scene I: i

Scene II: Mortal Man

The Tracks

Act I, Scene I

1. “Wesley’s Theory” serves as an introduction to the album’s central idea that it is the ‘butterfly’ that is to be ‘pimped,’ though the fullness of that means won’t be revealed until the final track while. It explains that right now the entertainment industry is ‘pimping’ black talent. These ‘niggas’ are the protagonist of the narrative, most often personified by Kendrick himself. He will often use his story as a parallel or as juxtaposition to the story of the nigga. The title uses Wesley Snipes’ story to illustrate this. He served a 3 year jail sentence for tax evasion after the government said he was using ‘tax protester theory’ to wiggle out of the charges. Another black celebrity, Dr. Dre, shows up to play a caricatured version of himself. Dre used to be the ‘pimped’ nigga (watch “Straight Outta Compton” for Dre’s story and to give visual aide to the Compton in which Kendrick grew up), but now finds himself in a position of power in the industry.

Kendrick’s relationship with Compton, who will develop into a major character, is strained but intact. Dre, though, has played both sides of the Compton prostitution game. There two sides are split among the two verses in the song. The first verse is told from the perspective of the talented nigga, namely Kendrick. The second verse is told from the perspective of capitalist America, personified by the first of our two antagonists: Uncle Sam. Uncle Sam is an obstacle to the black artist. The song also introduces the musical tenor of the album. There are traditional rap elements as well as soul, funk, and jazz; these are perhaps the four music genres niggas identify most heartily with. It has a distinct, fun Thundercat/George Clinton groove and a sample of Boris Gardiner’s “Every Nigger Is a Star” underneath Kendrick’s subdued lyrics.

Act I, Scene II

2. “For Free? (Interlude)” continues to build on this theme and works from the same metaphor. Kendrick, as protagonist, is resisting the lure of money and fame that the entertainment industry, Uncle Sam, has offered him. One of the album’s main characters, God, is first mentioned during the woman’s intro. God is presented as the antithesis of the nigga, but there’s an underlying sense from Kendrick that he believes there’s more of a relationship between the nigga and God than the woman believes. Kendrick uses Uncle Sam’s currency to examine the ledger between American history and its black citizens, ending with ‘I picked cotton that made you rich’ before the woman responds by trusting in Uncle Sam’s power.

There’s also an interesting gender reversal. The female is playing the role of pimp, while Kendrick repeats over and over that his sexuality isn’t free. Traditionally, hip hop has viewed that a woman’s sexuality costs a man something, but a man’s sexuality is free for the taking to the woman. Here we have a subtle introduction to another major character for the forthcoming story. While this stance on sexuality is a common refrain from almost every rapper, another west-coaster, 2Pac, is instantly recognizable as the primary author of that sentiment. To him, representing black culture, a man has to invest time and money to get to bed a girl, while the girl can get a man whenever she wants. This is the second nod to 2Pac, but the first is impossible to see until “Mortal Man” and the end of the album. Both God and 2Pac play major roles in the story while largely remaining in the background—though God certainly finds his way into the foreground than Pac.

Act II, Scene I

3. “King Kunta” is a blunt reference to Kunta Kinte, the famous slave from “Roots: The Saga of an American Family” who had his foot chopped off after attempting to escape his master’s plantation, representing Uncle Sam. To present the slave as a King is to present him as a properly elevated individual instead of one held down by Uncle Sam. Kendrick uses the character, an expansion of the album’s protagonist, to allow himself to let loose with more traditional rap bravado, energy, and esteem. Here, Kendrick is the King of the rap game—he ‘stuck a flag in... Compton’ and he’s happy to let everyone know it (the ghostwriter dis aimed at Drake is pretty great).

As the character subjected to and imprisoned by Uncle Sam and the capitalist entertainment industry, King Kendrick is once again a stand-in for all niggas, singing a song of empowerment, even arrogance in the face of false authority, and samples a diverse group of artists: Mausberg’s “Get Nekkid”, Michael Jackson’s “Smooth Criminal”, James Brown’s “The Payback”, and Ahmad Lewis’ “We Want the Funk”. We only get a partial thought, but at the end of the track Kendrick begins his grand poem, which will continue bit by bit throughout the album. It won’t be finished until “Mortal Man”, but its opening line rests underneath the whole album. Kendrick is a conflicted man, unsure how to harness his influence.

Act II, Scene II

4. “Institutionalized” brings the themes of money, power, and disenfranchisement into sharper, more sobering focus. The corruptive nature of wealth has always loomed over urban America and hip hop has often fueled that fire upon itself, but Kendrick has refuted this since he started rapping. Here, however, he not only sees the poor (niggas everywhere, and namely ‘West Side Compton’) as institutionalized by the rich, racist elite (the antagonist Uncle Sam) and the desire to become rich, but he also sees the rich and powerful institutionalized by fear and the desire to become even more rich. Kendrick acknowledges that there is a problem when prisons are filled with poor minorities, but he sees social prisons that aren’t made of brick and mortar as a more difficult jail to break out of.

Kendrick also brings God, flippantly, back into the discussion, this time as a comment that ‘niggas think I’m a god’. To the institutionalized black community who don’t see the spoils of God, which are seen by rich, elite, white America, God has been reduced to essentially the apex of mankind, Kendrick (it also works as a traditional rap brag, bringing Kendrick’s social position up to God’s, though "These Walls" will have something to say about that as soon as the next song). The title, in fact, is a play on words as ‘institutional’ connotes insanity. Perhaps—Kendrick suggests—the institution itself is insane rather than the inmates.

Act II, Scene III

5. “These Walls” is taken from the expression ‘if these walls could talk’ and is probably the album’s most complex and deeply layered metaphor. Throughout the song, ‘these walls’ are both literal walls (a woman’s ummmmm... private parts as well as prison) and allegorical (the walls of his headspace and psyche). Trapped inside these walls, the song is able to navigate difficult ideas like sex, abuse, grace, Kendrick’s career, enemies, and conscience. Narratively, the song follows Kendrick having sex with a woman who has children from a man in jail—a man imprisoned for murdering one of Kendrick’s friends.

In typically complex fashion, our protagonist views the episode as an act of revenge on behalf of his friend while maintaining a troubled conscience about using his fame and power to seduce a lady for that purpose. At the intersection between this woman, his dead friend, and the murderer linking them, we glimpse into Kendrick’s primary internal conflict: the desires and temptations to fit into Uncle Sam’s society as presently constructed and the desire to upend his society knowing its moral dubiousness. ‘These walls’ are revealed to be a cyclical prison whose members constantly run through lust, murder, and revenge, and only stop to reflect on the guilt at the end before restarting again. He also resists the urge to agree with the culture’s insistence from “Institution” to take his place as God: ‘I’m not the God of Nazareth.’ The song opens with a reiteration of the unfolding poem and closes with an additional couple of lines to close out the song—more thoughts on abusing power.

Act II, Scene IV

6. “u” picks up in the literal place (‘the hotel room’) where the poem leaves off and further penetrates (see what I did there. Kendrick isn't the only guy in the article with some wordplay) the dark corners of our protagonist’s psyche, coming clean on all the negative thoughts in a format where he dialogues with and berates himself. Kendrick has always teetered between witty arrogance and self-hatred and here he reveals himself to be ‘a f***ing failure’.

The song lays down his deepest insecurities and his darkest thoughts. Kendrick is selfish and always letting himself and Compton down. He is completely naked on the track, and if the listener hasn’t yet empathized with life-struggle of the nigga protagonist he or she can now, at the very least, identify with the complicated conscience and overwhelming depression laid at his or her feet. This may be the lowest point of the album’s story and makes the hit that follows it so much more potent. The despair that has flowed throughout the veins of the album thus far finds its climax at this point just before this despair is introduced as its own complex villain in the next track.

Act II, Scene V

7. “Alright” comes out of the shadows of what has been to this point an album spiraling downward. Profound and timely, as Kendrick’s protagonist seeks higher purpose and direction, the song is a response to a black society riddled with the emotion of “u”. How does the character escape from these difficulties of life? He puts the drink from “u” down and looks toward God. In trusting God has a plan, Kendrick realizes his failures don’t matter. After all he reasons, ‘if God got us then we gon’ be alright.’ Born out of the external turmoil and internal struggle of the nigga explored earlier, the hook is earnest in its optimism.

Releasing about the same time as the Black Lives Matter movement caught steam, it was quickly dubbed ‘the song of the summer’, and it’s easy to see why. The talented protagonist is sitting in despair as a response to Uncle Sam’s police brutality and racist tendencies, but this song screams an anthem of hope amidst that very real, very potent despair. We are also introduced to the final main character in the story. The second verse briefly mentions Lucy, but it’s in the Kendrick’s poem at the end where we get a stronger hint as to her real identity: ‘the evils of Lucy was all around me.’ Whoever she is, Lucy is our second antagonist. Uncle Sam may be applying the external pressure, but Lucy’s internal wounds sting just as much.

Act III, Scene I

8. “For Sale? (Interlude)” offers an in-depth reflection on Lucy’s identity and motivations. Lucy is revealed to be short for Lucifer. Kendrick has been staring down the devil himself. His first antagonist, Uncle Sam, was an opponent much larger than he is, but Lucy takes this to a new level—even threatening to separate his momma, who will be the subject of the next track, from her hometown Compton—and embodies many of the same temptations that Uncle Sam does.

The title certainly suggests a pairing with “For Free? (Interlude)”, which also relates to his value as a musician and how that is transcended by his value as a human. While “For Free?” criticizes Uncle Sam for creating and maintaining a culture that believes famous people should show off their money, this song criticizes the hip hop culture as influenced by Uncle Sam. This hip hop culture, which encourages niggas to idolize bling and makes them believe that once they sign their first contract all their dreams will come true is the focus of the interlude sequel. Lucy’s voice is strong and now that Kendrick is ‘all grown up’ Lucy has a ‘contract’ for him to sign. He has battled Lucy since his 2011 debut, “Section.80” and seems to sit, always and precariously, at the tipping point between walking away from Lucy and signing the contract and handing his life over to the devil. At the end, Kendrick’s poem continues in front of a haunting musical section.

Act III, Scene II

9. “Momma” is Kendrick’s temporary stopping point in the poem. The poem dangles at ‘until I came home,’ which is the proper time to talk to Momma. This is, in part, a response to “Real” from “Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City” where his mom asked him to return and share his story to kids in Compton. It’s also likely referring to Kendrick’s 2014 visit to South Africa, the ‘motherland'; this trip is said to have inspired the most of the album. The conversation he has with the boy in verse 3 seems to back up both interpretations.

Certainly there is another, more straight-forward meaning too. Kendrick is making efforts yet still struggling to return to his former pre-fame youth, untainted by Uncle Sam and by Lucy. He doesn’t care about the recognition his effort has garnered; he simply seeks God’s grace and justice and Compton’s warmth and acceptance: ‘Thank God for rap, I would say it got me a plaque but what’s better than that? The fact that it brought me back home’ and later, ‘the way I’m rewarded, well, that’s God’s decision. I know you know that line’s for Compton.’ Lalah Hathaway’s “On Your Own” is sampled to great effect on the track, making Compton feel more universally audible.

Act III, Scene III

10. “Hood Politics” is offered as juxtaposition to “Momma". The survival guilt he confesses in his meta-poem and throughout the album is centered on Uncle Sam’s system and making it out of the poverty of Compton while staying ‘A-1’. While “Momma” is about how he forgot Compton and forgot hood life, in this song he actually transports himself to his childhood when Compton’s hood was all he knew. Kendrick’s voice throughout the track is pitched a touch higher to help embody the younger version of our protagonist.

He is able to use this perspective to discuss politics in verse 2 (‘from Compton to Congress’, even invoking President Obama—it’s all Uncle Sam) and the whole rap industry in verse 3 (mostly these are observations on the ridiculous controversy surrounding 2013's, “Control”). The song samples Sufjan Stevens’ “All For Myself”, which has a lot of parallel themes (especially in mixing greed, murder, and love). At the song's conclusion Kendrick’s poem continues, which reinforces the difficulty of his survivor’s guilt and the proclivity of his inner demons, as well as grounding their sources in his hometown as the last two tracks have stated.

Act III, Scene IV

11. “How Much a Dollar Cost” is the place where Kendrick, as protagonist, is finally able to overcome his adversaries Uncle Sam and Lucy, doing so in a beautiful parable. On his road to recovery, Kendrick runs into a homeless man at a gas station in South Africa. He tells the story of a man Kendrick assumes is a crack addict asking for ‘ten rand’ (about $1 American). After saying no, Kendrick feels resentment as the man continues to bother him. After he asks Kendrick if he’s read Exodus 14, Kendrick’s resentment begins to turn to guilt and empathy. The selfishness that has brought him so much success in hip hop rears its ugly head in his interaction with the homeless man.

It’s at that point that the man reveals his true identity: ‘You’re lookin’ at the Messiah, the son of Jehovah, the higher power, the choir that spoke the word, the Holy Spirit, the nerve of Nazareth…I am God.’ The story parallels the parable of ‘The Sheep and the Goat’ in Matthew 25. Kendrick spends the outro in repentance, asking God for forgiveness. It is in this moment of humility that Kendrick is finally able to break free from ‘the evils of Lucy’ and Uncle Sam—he has to be humbled to be humble. We also see his larger metaphor intensified as he observes that the figurative dollar is worth far more than the literal dollar implies. After all, if God is a bum, perhaps money really doesn’t buy happiness. Perhaps Uncle Sam and Lucy are both liars.

Act IV, Scene I

12. “Complexion (A Zulu Love)” takes this fresh humility and uses it to express truth as it relates to beauty standards and race. It eschews the colorism promoted by Uncle Sam and Lucy, which has burdened niggas for too long, and details the importance of loving all people no matter how light or dark, quoting his lighter-skinned girlfriend, Whitney Alford, ‘It all came from God.’ Rapsody (the featured artist) opens verse three contrasting the lighter-skinned, easy-going, recently passed-away Stuart Scott (known by many as the nigga on ESPN) with darker-skinned, militant 2Pac, who fought for black empowerment.

It makes sense that Rapsody, a female, would reference the man who wrote the ‘woman’s anthem’, “Keep Ya Head Up.” Here we have yet another glimpse into the character acting throughout the album’s background, waiting to pounce before it’s over. (Her verse also uses movies as a motif, Movietown should check out all the references packed into this one verse) Kendrick’s outro is mad dark, painting a hometown fully engulfed by Lucy's apocalyptic dream: ‘barefoot babies with no cares, teenage gun toters that don’t play fair, should I get out the car? I don’t see Compton, I see something much worse, the land of the landmines, the Hell that’s on Earth.’

Act IV, Scene II

13. “The Blacker the Berry” picks up in “Complexion’s” apocalyptic Hell and takes its idea of appreciating dark skinned niggas, in order ro make sure it’s difficulty isn’t glossed over as Uncle Sam and Lucy would hope for it to be. It also comes before “i”, which further expands this thought. The song deals very heavily with racial self-hatred and begs further comparisons to 2Pac’s “Keep Ya Head Up”, whose opening line includes the phrase, ‘blacker the berry’ and deals with much of the same content and theme.

Sharing vocal duties with Jamaican artist Assassin (who lent a hand to Kanye on a very similar track, “I’m In It” for 2013’s “Yeezus”) also helps to ensure that this is not swept up as an American nigga problem, just as the closing seconds of “Complexion” hinted. Kendrick recognizes the universality of the issue while never straying from Compton and issues of American racism he sees in his own backyard. Kendrick’s name-dropping of Trayvon Martin at the end of the song and calling himself out as the effective murderer is a powerful confessional social statement and reminds not only this song, but the whole album that Uncle Sam and Lucy work in tandem.

Act IV, Scene III

14. “You Ain’t Gotta Lie (Momma Said)” is a kind of final rumination on the thoughts presented in the two interludes, “For Free” and “For Sale”. It settles into a potential purgatory for black entertainers and for all niggas. This purgatory traps those who are neither mega-celebrities, nor anonymous enough to return to their hood without receiving an overflow of attention from everyone. There are racial undertones as Uncle Sam and Lucy continue to insist on their presence and Kendrick uses stereotypical black imagery to paint himself as a hood figure, feeling pressure to change, to perform, or to act in a certain way, once again acknowledging his hope to continue acceptance in Compton.

In an atmosphere ripe for hypocrisy, Kendrick very rationally argues that ‘you ain’t gotta lie to kick [respect]’. Where the first interlude, "For Free", criticized those who think rap is inherently dependent on money and power as Uncle Sam insists and the second interlude, "For Sale", pondered the trappings of fame presented by Lucy, this track, nearing the album’s end, retorts with a simple but powerful shoulder shrug. Effectively, he has gotten to the point where he is comfortable saying, I am who I am and Compton can either accept that or not.

Act V, Scene I

15. “i” is the (twice) Grammy-winning song Kendrick promises from the album's genesis and it’s the last track from the main body of the album. For all of the negativity and difficult introspection found on the album, this is a song that can stand on its own as a response to the legion of doom, which has come before it. Indeed, it’s a song about self-expression directly inspired by the lack of self-love on the streets of Compton. Here our protagonist is turning his shoulder shrug into an expression of the need for expression. He has overcome Uncle Sam. He has overcome Lucy. There is nothing in his way, no judgement, no fear, and no bad self-consciousness. He’s ‘been through a whole lot, trial, tribulation, but [he] knows God.’

Whereas the “i” single had a crisp, clean production, the album version is mixed to sound like a live performance for ‘all of the boys and girls’ and it really brings the listener into its celebration. “To Pimp a Butterfly” sits in spiritual turmoil, self-doubt, and temptations from all angles, but closing out the album Kendrick offers redemption in the form of a big, brash, joyful concert, sampling The Isley Brothers’ “That Lady”, and then ends the concert with a passionate sermon that directly calls—by name—for his hometown niggas to recognize the injustices around them. Then in a third part, Kendrick spits an acapella verse ruminating on the use of the word ‘nigga’ (or ‘negus’). Kendrick thinks there’s more to a nigga than Oprah does, he backs up his claim historically, and he declares a vehement lack of shame. He won’t whitewash his people.

Act V, Scene II

16. “Mortal Man” is the closing scene. Centering more squarely on his trip to South Africa, Kendrick speaks directly to Nelson Mandela’s ghost and invokes the names of Moses, Huey Newton, Malcom X, Martin Luther King Jr, John F. Kennedy, Jackie Robinson, Jesse Jackson, and Michael Jackson. The song’s political and African influence can also be heard through the sampling of Houston Person’s Afrobeat hit “I No Get Eye for Back”. His monologue to Mandela recognizes that as he’s come to the end of this journey, betrayal from Compton is both possible and scary. Mandela’s forgiveness—as a type of God’s forgiveness—is a standard he wants to reach, but he's in honest struggle with it. Kendrick is admitting to himself that he’s just a mortal man. He’s also hoping his fans will stand beside him if he messes up (each of the leaders invoked in the song endured periods where his ‘fans’ betrayed him).

After the more straightforward song that opens the 12 minute ending track, Kendrick is finally able to spit his poem in full. The poem is full of humanity and the irreverence he shows himself in its presentation work to give it even more credence as one of humble depth. Through everything Kendrick has encountered and wrestled with, all the successes and all the failures, this poem is such a beautiful place for him to find himself. It is somehow concise enough to fit within 12 lines and thorough enough to encapsulate the emotional journey of the previous 80 minutes.

And it is at the poem’s conclusion that we visit our background character, 2Pac. In a shocking turn, we meet Pac not merely in reference, but in voice. Kendrick samples an interview from 1994 and weaves Pac’s answers into a dialogue between the two west-coast rappers. Many have called Kendrick the new 2Pac and growing up in Compton, Pac’s presence, and then later his memory, surely lingered over Kendrick and his peers. Kendrick raised Compton’s hero from the dead in order to give an earnest listen to what he has to say about race, politics, violence, hip hop, Uncle Sam, Lucy, God, himself, Kendrick, the apocalypse, and artistic purpose. There is enough in that brief faux-interview to write a book on, but at minimum there seems to be a distinct and fascinating Venn diagram where the two think similarly and differently. Kendrick has mad respect for Pac but at the same time, he’s not a blind disciple of the man.

After the interview Kendrick asks Pac if he can read him another poem for the fourth and final part of the track. This poem once and for all brings the whole artistic, political, and spiritual roots of the album into focus, using a caterpillar/butterfly as allegory. The caterpillar is the nigga from Compton or any other hood, imprisoned by racism, poverty, addiction, gang violence, police brutality and all the evils of Uncle Sam and Lucy, the caterpillar has life stacked against him. The butterfly is the potential within the nigga caterpillar. If the caterpillar is given the freedom and opportunity to grow wings, he will indeed show the world his beauty and ability. However, often, the walls of the cocoon are prisons, which insulate the nigga from the rest of the world. From his perspective, there is nothing else: no one ever leaves or comes into the prison. He doesn’t like it, but he accepts it. Without hopes, dreams, or aspirations his talents dissolve and his life is reduced to survival. Surrounded by chaos and war, he picks up his chosen weapon and fights. The objectives and morals of these fights are gray and blurry, but they don’t matter to the nigga. He doesn’t know love or mercy or forgiveness, and reasoning is a luxury not afforded in this prison. This means that the war continues eternally and the nigga never escapes the cocoon. Many outside of this prison will call him a ‘thug’ and those in power will see him as a statistic, but most will just ignore him. Occasionally a nigga will break down the walls of the cocoon, transform, and fly out of the prison, but this is very, very rare. Most caterpillars die in the cocoon.

Kendrick is a butterfly, though. He made it out. The butterfly is the potential of the caterpillar if the prison is broken down. It may be easy to say that Kendrick made it out because he’s massively talented, but while that’s true, there are still so many other talented niggas without wings. People simply don’t care about caterpillars until they become butterflies. They’re just common bugs. People care about butterflies, though. Butterflies are beautiful, expansive, and free to be themselves. Kendrick doesn’t take his good fortune for granted and he wants to be the rare butterfly that helps niggas still walled-in. Butterflies don’t typically do that. Most butterflies side with Uncle Sam and Lucy because both share a value system to ensure that butterflies have the best possible life—money, fame, etc.—but Kendrick is determined to side with the nigga, to return to Compton and help caterpillars become butterflies.

While Uncle Sam and Lucy work to keep the world’s systems intact and to recruit butterflies to aide them as pimps, promising vain goodness, Kendrick is bending his ear to God, the advocate for the nigga and for Compton. Kendrick admits over the last couple tracks that he is still working to process this value system—forgiveness, mercy, grace, and enemy-love make for a backwards route to the justice he seeks—but he knows what side he’s on. He is determined to be a force for good. The album’s title rests within this poem, but so too does the poem’s listener rest within the album’s title. “To Pimp a Butterfly” could be given the acronym, 2PaB. Kendrick is 2PaB, the butterfly, aspiring to help the caterpillars of Compton reach their potential and find the true freedom they each deserve. 2Pac was still caught up in Lucy’s dog-eat-dog systems of the world dictated by hate, anger, and the pursuit of retribution; 2PaC (“To Pimp a Caterpillar”) and his violence were still pimping caterpillars, and Kendrick is finding a most humble way to say he is better than the legend. Kendrick is the fully formed, post-cocoon 2Pac. In this, he represents both the modest heart of Nelson Mandela and the braggadocios soul of the rapper.

While the butterfly has always pimped the caterpillar (revisit “Wesley’s Theory” to see these themes emerge more clearly now that we're through the album), Kendrick has set out to reverse the world-systems and to instead pimp the butterfly. He has God and Compton on his side, and he doesn’t need anyone else. Still, an invitation is extended.

Kendrick wants to know:

Will you help pimp the butterfly?

Will you stand up for the nigga?

Will you resist the temptations of Lucy and Uncle Sam?

Will you stand by Compton in its time of need?

Will you side with homeless Jesus?

Will you empathize with Trayvon Martin and other black victims?

Will you truly embrace the idea of universal brotherhood? After all, the poem’s final unifying line is, ‘although the butterfly and caterpillar are completely different, they are one and the same.’ Kendrick wants us all—black, white, or purple—to resolve not to cut off our own foot.

#kendrick #lamar #topimpabutterfly #musictown #album #music #story #spikelee #chiraq #2015 #2Pac #Tupac #Compton #God #UncleSam #DrDre #Jesus #KuntaKinte #NelsonMandela #TrayvonMartin #WesleySnipes #WhitneyAlford #StraightOuttaCompton #rap #soul #funk #jazz #Thundercat #GeorgeClinton #BorisGardiner #gender #sexuality #race #racism #Drake #Mausberg #MichaelJackson #JamesBrown #AhmadLewis #money #wealth #hiphop #America #poor #hood #rich #protagonist #antagonist #prison #sex #revenge #violence #conscience #fame #morals #murder #lust #arrogance #selfhatred #insecurity #depression #despair #villain #black #blacklivesmatter #songofthesummer #policebrutality #hope #poem #poetry #lucy #lucifer #devil #momma #famous #Section80 #GoodKid #MAADCity #SouthAfrica #LalahHathaway #President #Obama #congress #control #sufjanstevens #greed #love #guilt #homeless #exodus #empathy #selfishness #identity #messiah #jehovah #holyspirit #nazareth #parable #matthew #repentance #forgiveness #evil #humble #dollar #happiness #beauty #colorism #rapsody #stuartscott #keepyaheadup #apocalyptic #dream #hell #assassin #kanye #yeezus #trayvonmartin #confession #grammy #concert #live #isleybrothers #acapella #oprah #shame #whitewash #moses #hueynewton #malcomx #martinlutherking #johnfkennedy #jackierobinson #jessejackson #michaeljackson #political #african #houstonperson #afrobeat #monologue #journey #betrayal #art #spiritual #caterpillar #butterfly #cocoon #allegory #poverty #addiction #gangviolence #gangs #freedom #survival #war #mercy #eternal #thug #statistic #potential #talent #bugs #valuesystem #recruit #pimp #track #dogeatdog #hate #anger #retribution #modest #heart #theme #reverse #invitation #temptation #brotherhood #foot

Comments